Now the government wants to ban them as part of its action plan for a smoke-free New Zealand by 2025. A number of studies have investigated the checkered history of cigarette filters.

While the Surgeon General's 1964 report concluding that "smoking is causally linked to lung cancer in men" is considered a defining moment for smoking and health, the rumors started much earlier.

A 1938 study linked smoking to shorter life expectancy, and the New Zealand Ministry of Health issued the first smoking warning in 1945.

Suddenly, an unassuming porous plug became the key to the survival of a multi-million dollar industry.

Taking the fear out of smoking

Richard Terrill was a late starter. By the year he was born, 1945, smoking had become so ubiquitous that even women wearing Berlei brassiere ads were smoking.

Most of his friends were smokers, but he was not a fan. He tried his father's Player's Plains - no filter - and they made him sick.

But he remembers the marketing. When filters became commonplace in the '60s, the messaging was the same.

"They're good for your health. They took all the dirt out of your cigarettes," recalls the RSA support staff.

Trier didn't start smoking until he was 25 - right around the time he first heard about cancer. His then-wife - a smoker - dared him to do it. She gave up, and he became addicted.

He always smoked filter cigarettes, but from early on he couldn't recognize them. The first iteration looked like screwed up paper. Then came the De Reszke cork: "They're actually as rough as sodomy, but you don't get the skin off the lips."

The firefighters, Trier and the boys would keep a company-bought pouch in the glove box of the fire truck. They would light up after putting out a fire - usually caused by smothered cigarette butts. In the absence of a respirator, a puff of smoke helped them cough up the thick, black fire smoke lurking in their lungs.

While Trier notes the slow change in his cigarette butts, tobacco company documents and patent registries reveal an all-out war on innovation.

As Stanford researcher Bradford Harris explained in his 2011 British Medical Journal paper, the thorny cigarette "filter problem," in the 1950s and '60s, U.S. cigarette companies spent millions of dollars searching for a paper-covered plug that would filter out the wind. .

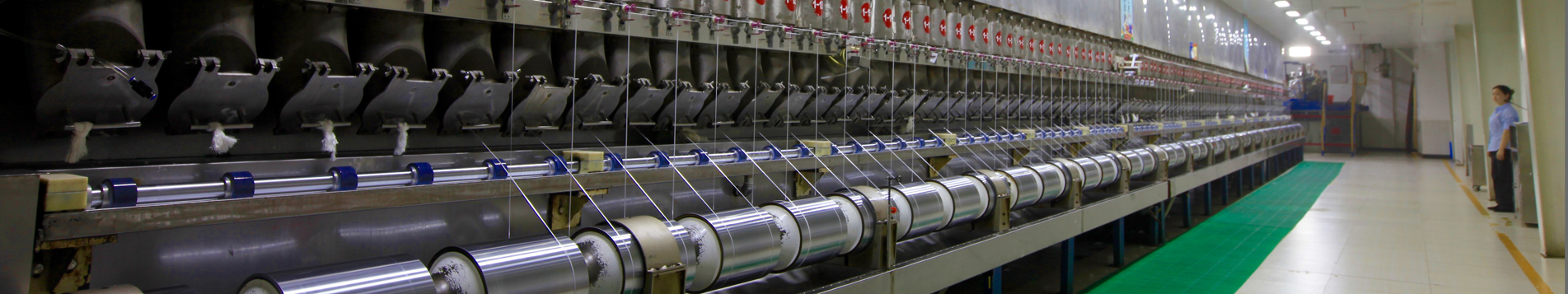

Natural fibers such as cotton were rejected because they were too difficult to standardize and could not be processed at the required rate of 250 cigarettes per second. As a result, chemical giants Dow and DuPont were recruited to design synthetic options.

In 1952, the tobacco company Lorillard introduced the Kent Micronite filter. Made of crocidolite fibers wrapped in crinkled crepe paper, it successfully filtered out 30 percent of the cancer-causing tar. There was only one problem - crocidolite is a form of asbestos. The filter lasted only four years, leaving a legacy of smokers and factory workers who suffered from asbestos-related cancers.

Innovators also considered everything from charcoal to kelp to moisture capsules to enhance the filter's ability to absorb tar.

The first filter made from cellulose acetate, a bioplastic byproduct of the wood industry that was later used in photographic film and is now used to make eyeglass frames, was introduced in 1950.

A curled bundle or ribbon of cellulose acetate - like a crepe bandage - is stretched and combed into something resembling cotton wool. It is sprayed with plasticizer and made into a stick, then a cigarette filter.

But Harris notes that intensive filter research uncovered two problems. "By the mid-1960s, cigarette designers realized that the difficulty of rationalizing the 'filter problem' stemmed from the simple fact that the harmful substances in mainstream smoke and the substances that provide 'satisfaction' were essentially the same thing. "

For example, those Kent Micronites made with asbestos were judged by smokers to be too effective, producing bland flavors and strong attractions.

The researchers also noticed something else - some of the fibers in the plastic filters were also getting into the smokers' lungs. In private, they called it radiation. In public, they denied its existence.

In the 1960s, companies began punching holes in the filters. Side ventilation helped draw air into the smoke, diluting toxic gases and increasing filter efficiency. When tested on smoking machines, they showed a reduction in tar. But it turns out that smokers aren't like robots-they just change the way they smoke, blocking the vents or dragging them out longer or faster to get the same hit.

Even as tobacco companies realized that their real attempts to make cigarettes safer seemed doomed to failure, the public smoked filters with optimism.

As a 1954 New York Times headline proclaimed: The Cigarette Industry Is Recovering: Filter Prescriptions Seem to Help.

A 1962 survey of New Zealand women smokers found that eight out of ten smoked filters, some of whom chose

Share:

English

English Español

Español Pусский

Pусский Tiếng Việt

Tiếng Việt 日本語

日本語 Deutsch

Deutsch Français

Français Türkçe

Türkçe العربية

العربية

Provide Us Your Specifications

Provide Us Your Specifications Custom Made For You

Custom Made For You Prompt Delivery

Prompt Delivery